“Is something going around?” is a question I am often asked. In previous holiday seasons, I have often responded, “The Christmas Crud.” Now with the improvement in multipathogen respiratory panels, I can give a more nuanced response. Before I do that, there is a non-respiratory virus that is circulating, norovirus, which is notorious for causing outbreaks on cruise ships.

This is a news alert from CBC news.

Cases of norovirus, a wretched and highly contagious stomach bug, are surging in parts of the United States this winter, according to government data.

The most recent numbers from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show there were 91 outbreaks of norovirus reported during the week of Dec. 5, up from 69 outbreaks the last week of November. Numbers from the past few years show a maximum of 65 outbreaks reported during that first week of December.

“We typically do see an increase in norovirus cases in the winter, around this time of year, because of large gatherings, people traveling, different generations of people together,” Dr. Céline Gounder, CBS News medical contributor and editor-at-large for public health at KFF Health News, said on “CBS Mornings.”

Here’s what else to know.

What is the norovirus stomach bug?

Norovirus virus is a “highly infectious virus causing diarrhea, abdominal pain and vomiting,” Gounder said.

Cases are ticking up on land, too. The Minnesota Department of Health recently logged 40 cases of norovirus, which is twice the usual number for December, CBS News Minnesota reported.

Norovirus stomach bug symptoms and treatment

Along with vomiting, stomach pain and diarrhea, common symptoms include nausea, body aches, headache and fever.

Most norovirus outbreaks occur when people who are already infected spread the virus to others by direct means, such as through sharing food or eating utensils. Outbreaks can also be spread through food, water or contaminated surfaces.

“The most important thing you can do to prevent transmission is wash your hands. If you’re sick, don’t be preparing food for other people and don’t be sharing food with other people,” Gounder said.

Illness caused by norovirus typically starts suddenly, with symptoms developing 12 to 48 hours following exposure to the virus. Most people get better within one to three days and recover fully.

People of all ages can get infected and fall sick from norovirus. Young children, older people and those with weakened immune systems are most at risk, with dehydration from vomiting and diarrhea the top concern.

There is no medication to treat norovirus. Rehydration is recommended by drinking water and other liquids (but not coffee, tea or alcohol).

“The key is to stay hydrated — especially little infants (and) the elderly may have trouble keeping up with that — so that is the key to treating them,” Gounder said.

Anyone suffering from dehydration should seek medical help. Symptoms of dehydration include a decrease in urination, dry mouth and throat, and feeling dizzy when standing. Dehydrated children may be unusually sleepy or fussy and cry with few or no tears.

Rigorous and frequent handwashing is the best defense against norovirus during the peak winter season, scrubbing hands with soap and warm water for 20 seconds before meals.

Hand sanitizers may reduce the transmission of norovirus and other viruses, but handwashing is most effective in preventing the transmission of norovirus.

Back to respiratory infections:

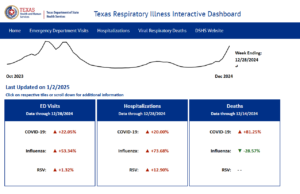

Respiratory Illnesses Data Channel

What to know

- As of January 3, 2025, the amount of acute respiratory illness causing people to seek healthcare is at a high level and continues to increase nationally.

- COVID-19 activity is increasing in most areas of the country.

- Seasonal influenza activity continues to increase and is elevated across most of the country.

- RSV activity is very high in many areas of the country, particularly in young children.

- The community snapshot signifies activity levels using the following colors: minimal, low, moderate, high, very high.

Your community snapshot

The CDC may not have data for all states, counties, or territories. Read more »

Overall respiratory illness activity in the United States

What it is: A measure of how frequently a wide variety of respiratory symptoms and conditions are diagnosed by emergency department doctors, ranging from the common cold to COVID-19, flu, and RSV.

Why it matters: Summarizes the total impact of respiratory illnesses, regardless of which diseases are causing people to get sick.

Wastewater viral activity level in the United States

COVID-19

Flu†

RSV

What it is: A measure of how much virus is present in sewage.

Why it matters: People who are infected often shed virus into wastewater, even if they don’t have symptoms. As a result, high wastewater levels may indicate an increased level of infections even when other measures remain low.

† Flu levels are for Influenza A only, which includes avian influenza A(H5). Wastewater data can not determine the source of viruses (from humans, animals, or animal products).

Emergency department visits in the United States

COVID-19

Flu

RSV

What it is: A measure of how many people are seeking medical care in emergency departments.

Why it matters: When levels are high, it may indicate that infections are making people sick enough to require treatment.

Weekly national summary

Reported on Friday, January 3, 2025.

COVID-19 activity is increasing in most areas of the country. Seasonal influenza activity continues to increase and is elevated across most of the country. RSV activity is very high in many areas of the country, particularly in young children.

COVID-19

COVID-19 activity is increasing in most areas of the country, with high COVID-19 wastewater levels and increasing emergency department visits and laboratory percent positivity. Based on CDC modeled estimates of epidemic growth, we predict COVID-19 illness will continue to increase in the coming weeks as it usually does in the winter.

There is still time to benefit from getting your recommended immunizations to reduce your risk of illness this season, especially severe illness and hospitalization.

CDC expects the 2024-2025 COVID-19 vaccine to work well for currently circulating variants. There are many effective tools to prevent spreading COVID-19 or becoming seriously ill.

Influenza

Seasonal influenza activity continues to increase and is elevated across most of the country. Additional information about current influenza activity can be found at: Weekly U.S. Influenza Surveillance Report | CDC

RSV

RSV activity is very high in many areas of the country, particularly in young children. Emergency department visits and hospitalizations are highest in children and hospitalizations are elevated among older adults in some areas.

Vaccination

Vaccination coverage with influenza and COVID-19 vaccines are low among U.S. adults and children. COVID-19 vaccine coverage in older adults has increased compared with the 2023-2024 season. Vaccination coverage with RSV vaccines remains low among U.S. adults. Many children and adults lack protection from respiratory virus infections provided by vaccines.

Season Outlook

CDC continues to expect the fall and winter virus season will have a similar or lower peak number of combined hospitalizations from COVID-19, influenza, and RSV compared to last year. However, peak hospitalizations from all respiratory viruses remain likely to be much higher than they were before the emergence of COVID-19.

CDC’s December outlook update uses historical data and COVID-19 scenario modeling to assess when peak hospital demand may occur nationally and regionally. Additional updates will occur if there are big changes in how COVID-19, flu, or RSV are spreading. Read the entire 2024-2025 Respiratory Season Outlook- December Update. (12/20/2024).

Protect yourself and your community

- Safeguard your health – Get the latest information from Vaccines.gov

- Order 4 free at-home COVID-19 tests today on COVIDTests.gov

- Explore resources and recommendations for older adults – Stay informed and protected

- Review tailored health recommendations for high-risk individuals

- Feeling ill? Take immediate steps to protect yourself and others – Start here

- Have symptoms? Consider wearing a mask

- Take action against germs – Practice good hygiene

- Got questions? Check out our FAQs

Continue exploring these data

Key Points: Antiviral Drugs for Seasonal Influenza

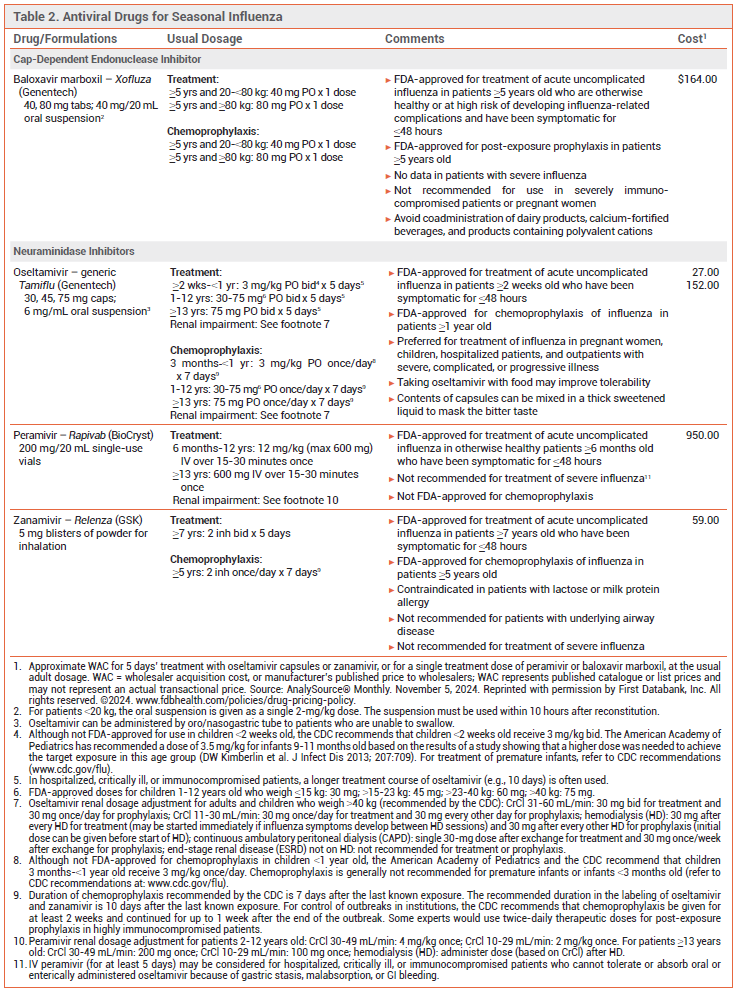

- Influenza antiviral drugs available this season include three neuraminidase inhibitors (oral oseltamivir, IV peramivir, and inhaled zanamivir) and the oral cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir marboxil. They are all active against influenza A and B viruses.

- Antiviral treatment is most effective when started within 48 hours after illness onset.

- Antiviral treatment is recommended for patients with suspected or confirmed influenza who are hospitalized, have severe, complicated, or progressive illness, or are at increased risk for complications, even if it is started more than 48 hours after illness onset.

- Antiviral treatment can be considered for otherwise healthy symptomatic outpatients with suspected or confirmed influenza who are not at increased risk for influenza complications if it can be started within 48 hours after illness onset.

- Oseltamivir is preferred for treatment of children, pregnant women, hospitalized patients, and outpatients with severe, complicated or progressive illness.

- Post-exposure prophylaxis with oseltamivir, zanamivir, or baloxavir should be considered within 48 hours for persons at very high risk of complications who have not received an annual influenza vaccine or when influenza vaccination may be ineffective; it is not recommended for healthy persons exposed to influenza.

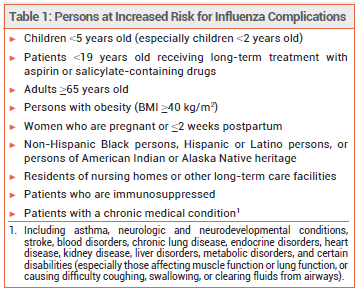

Influenza is generally a self-limited illness, but pneumonia, respiratory failure, and death can occur, especially in persons at increased risk for influenza complications (see Table 1). Updated information on influenza activity and antiviral resistance is available from the CDC at cdc.gov/flu.

TREATMENT OF INFLUENZA — Three neuraminidase inhibitors (oral oseltamivir, IV peramivir, and inhaled zanamivir) and the oral cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir marboxil are available in the US for treatment of influenza this season (see Table 2).

Antiviral treatment is recommended as soon as possible for any patient with suspected or confirmed influenza who is hospitalized, has severe, complicated, or progressive illness, or is at increased risk for complications (see Table 1), even if it is started >48 hours after illness onset.1-3 False-negative results can occur with influenza tests; patients with suspected influenza in the aforementioned groups should receive antiviral treatment despite a negative test, especially when influenza viruses are known to be circulating in the community.4

Antiviral treatment can be considered for otherwise healthy symptomatic outpatients with suspected or confirmed influenza who are not at increased risk for influenza complications if it can be started within 48 hours after illness onset.

Oseltamivir is preferred for treatment of influenza in pregnant women, children, hospitalized patients, and outpatients with severe, complicated, or progressive illness.1,3

Guidelines for treatment of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) recommend antiviral treatment for patients with CAP who test positive for influenza regardless of the duration of illness before diagnosis.5

Effectiveness – Neuraminidase inhibitors and baloxavir are active against influenza A and B viruses. Use of a neuraminidase inhibitor or baloxavir for treatment of acute uncomplicated influenza in adults shortens the duration of symptoms by about one day.6-9 Although most controlled trials of antiviral drugs have not been powered to assess their efficacy in preventing serious influenza complications, experts have generally concluded from the combined results of observational studies, controlled trials, and metaanalyses that early antiviral treatment of influenza in high-risk and hospitalized patients can reduce the risk of complications.6,10-13

In a randomized, double-blind trial (CAPSTONE-2) in 2184 outpatients ≥12 years old with uncomplicated influenza who were at high risk of developing complications, the median time to symptom improvement was similar with a single dose of baloxavir or 5 days’ treatment with oseltamivir (both started within 48 hours after illness onset) in the overall population and in those infected with influenza A(H3N2), but was statistically significantly shorter with baloxavir in those infected with influenza B (74.6 vs 101.6 hours). Use of either drug was associated with a lower incidence of influenza-related complications and fewer antibiotic prescriptions compared to placebo.9

In a randomized, double-blind trial (miniSTONE-2) in 173 otherwise healthy children 1-11 years old with influenza, the median time to symptom improvement was similar with a single dose of baloxavir or 5 days’ treatment with oseltamivir (138 vs 150 hours; both started within 48 hours after illness onset).14

A meta-analysis of 5 randomized trials in children with influenza found that starting oseltamivir within 48 hours after illness onset reduced illness duration by about 18 hours (by about 30 hours when trials that enrolled children with asthma were excluded) and decreased the risk of otitis media.15

In a retrospective cohort study in 542 adults hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza, time to defervescence, duration of hospital and intensive care unit stay, and mortality rates were similar with oral oseltamivir and IV peramivir.16

In a meta-analysis of 6 randomized controlled trials in hospitalized patients with severe influenza (mean age 36-60 years) treatment with oseltamivir or peramivir was associated with small reductions in the duration of hospitalization compared to placebo or standard care (-1.63 days with oseltamivir and -1.73 days with peramivir).17

In an observational cohort study in hospitalized children (with underlying conditions or admitted to the ICU) with laboratory-confirmed influenza, the duration of hospitalization was shorter with antiviral treatment started within 48 hours after illness onset than with no antiviral treatment.18

In a randomized, double-blind trial (FLAGSTONE) in 366 patients ≥12 years old hospitalized with severe influenza, the median time to clinical improvement was not statistically significantly different between a combination of a neuraminidase inhibitor (primarily oseltamivir) and baloxavir and a neuraminidase inhibitor alone (97.5 vs 100.2 hours).19

Timing – Neuraminidase inhibitors are most effective when started within 48 hours after illness onset, but the results of some observational studies in hospitalized and critically ill patients suggest that treatment started as late as 4-5 days after illness onset can shorten the duration of hospitalization and reduce the risk of pneumonia, respiratory failure, and death.20-22

No data are available on the efficacy of baloxavir started >48 hours after illness onset.

In a retrospective cohort study of 23,233 hospitalized adults with laboratory-confirmed influenza and pneumonia, delayed initiation of antiviral treatment was associated with a higher risk of death; compared to patients who started antiviral treatment on day 0, the adjusted odds ratio for death was 1.14 (95% CI 1.01-1.27) in those who started treatment on day 1 and 1.40 (95% CI 1.17-1.66) in those who started on days 2-5.23