Acute and postacute sequelae associated with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection

Nature Medicine (2022)

Abstract

First infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is associated with increased risk of acute and postacute death and sequelae in various organ systems. Whether reinfection adds to risks incurred after first infection is unclear. Here we used the US Department of Veterans Affairs’ national healthcare database to build a cohort of individuals with one SARS-CoV-2 infection (n = 443,588), reinfection (two or more infections, n = 40,947) and a noninfected control (n = 5,334,729). We used inverse probability-weighted survival models to estimate risks and 6-month burdens of death, hospitalization and incident sequelae. Compared to no reinfection, reinfection contributed additional risks of death (hazard ratio (HR) = 2.17, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 1.93–2.45), hospitalization (HR = 3.32, 95% CI 3.13–3.51) and sequelae including pulmonary, cardiovascular, hematological, diabetes, gastrointestinal, kidney, mental health, musculoskeletal and neurological disorders. The risks were evident regardless of vaccination status. The risks were most pronounced in the acute phase but persisted in the postacute phase at 6 months. Compared to noninfected controls, cumulative risks and burdens of repeat infection increased according to the number of infections. Limitations included a cohort of mostly white males. The evidence shows that reinfection further increases risks of death, hospitalization and sequelae in multiple organ systems in the acute and postacute phase. Reducing overall burden of death and disease due to SARS-CoV-2 will require strategies for reinfection prevention.

Main

A large body of evidence suggests that first infection with SARS-CoV-2 is associated with increased risk of acute and postacute death and sequelae in the pulmonary and broad array of extrapulmonary organ systems1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. However, many people around the globe are experiencing repeat SARS-CoV-2 infections (reinfections). Previous epidemiological studies of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection have been limited to investigations of the risk of getting reinfection and the comparative evaluation of risk differences of hospitalization or death between first and second SARS-CoV-2 infections during their acute phase9,10. Whether and to what extent reinfection adds to the risk incurred after the first infection is not clear (that is, evaluation of the risk of reinfection versus no reinfection). Whether reinfection contributes to the increased risk of acute and postacute sequelae is also not known. Addressing these questions has broad public health implications since it will inform whether strategies to prevent or reduce the risk of reinfection should be implemented.

In this study, we used the electronic healthcare database of the US Department of Veterans Affairs to address the question of whether SARS-CoV-2 reinfection adds to the health risks associated with a first SARS-CoV-2 infection. We characterized the risks and 6-month burdens of a range of prespecified outcomes in a cohort of people who experienced a SARS-CoV-2 reinfection compared to those with no reinfection, characterized the risks of acute and postacute outcomes in people who had reinfection and finally estimated the cumulative risks and one-year burdens associated with one, two, three or more infections compared to a noninfected control cohort.

Results

There were 443,588 cohort participants with no SARS-CoV-2 reinfection (only a single SARS-CoV-2 infection) and 40,947 participants who had SARS-CoV-2 reinfection (two or more infections) (Extended Data Fig. 1); 5,334,729 participants with no record of positive SARS-CoV-2 infection were in the noninfected control group. Among those who had reinfection, 37,997 (92.8%) people had two infections, 2,572 (6.3%) people had three infections and 378 (0.9%) people had four or more infections. The median distribution of time between the first and second infection was 191 d (interquartile range (IQR) = 127–330) and between the second and third was 158 d (IQR = 115–228). The demographic and health characteristics of those with no reinfection, reinfection and the noninfected control group are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection

To gain a better understanding of whether reinfection adds risk, we first conducted analyses to examine the risks of all-cause mortality, hospitalization and a set of prespecified outcomes in people who had reinfection compared to those with no reinfection.

We provide two measures of risk: (1) we estimated the adjusted HRs of a set of incident prespecified outcomes comparing people who had reinfection versus no reinfection and (2) estimated the adjusted excess burden of each outcome per 1,000 persons 6 months after SARS-CoV-2 reinfection on the basis of the difference between the estimated incidence rate in individuals who had reinfection and no reinfection. Follow-up began at the time of reinfection, where reinfection was defined as a SARS-CoV-2 positive test at least 90 d after the initial positive test; this time frame of 90 d was specified to reduce the probability that a positive test was related to the first infection. Assessment of standardized mean differences of participant characteristics (from data domains including diagnoses, medications and laboratory test results) after application of weighting showed they were well balanced in each analysis of incident outcomes (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1).

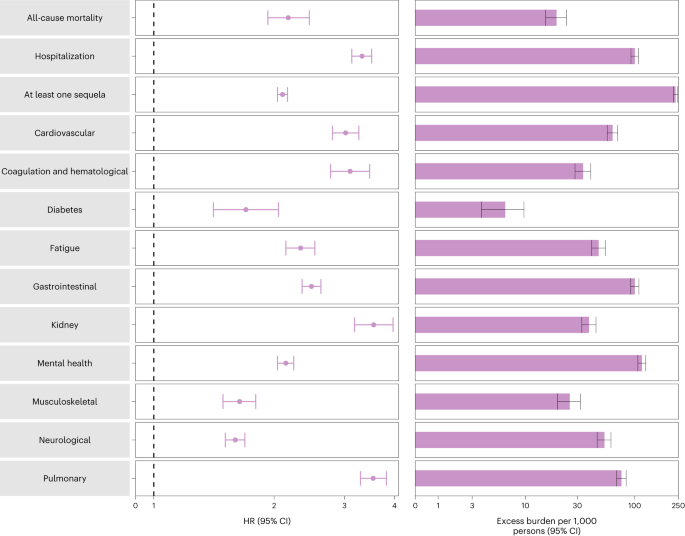

Compared to those with no reinfection, those who had reinfection exhibited an increased risk of all-cause mortality (HR = 2.17, 95% CI = 1.93–2.45) and excess burden of all-cause mortality estimated at 19.33 (95% CI = 15.34–23.82) per 1,000 persons at 6 months; all burden estimates represent excess burden and are given per 1,000 persons at 6 months (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3). People with a reinfection also had an increased risk of hospitalization (HR = 3.32, 95% CI = 3.13–3.51; a burden of 100.19 (92.53–108.25)) and having at least one sequela of SARS-CoV-2 infection (HR = 2.10, 95% CI = 2.04–2.16; a burden of 235.91 (225.54–246.34)) (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3).

Risk and 6-month excess burden of all-cause mortality, hospitalization, at least one sequela and sequelae by organ system are plotted. Incident outcomes were assessed from reinfection to the end of the follow-up. Results from SARS-CoV-2 reinfection (n = 40,947) and no SARS-CoV-2 reinfection (n = 443,588) are compared. Adjusted HRs (dots) and 95% CIs (error bars) are presented, as are the estimated excess burden (bars) and 95% CIs (error bars). Burdens are presented per 1,000 persons at 6 months of follow-up from the time of reinfection.

Compared to those with no reinfection, those who had reinfection exhibited increased risk of sequelae in the pulmonary (HR = 3.54, 95% CI = 3.29–3.82; burden = 75.74, 95% CI = 68.47–83.50) and several extrapulmonary organ systems including cardiovascular disorders (HR = 3.02, 95% CI = 2.80–3.26; burden = 62.80, 95% CI = 56.17–69.91), coagulation and hematological disorders (HR = 3.10, 95% CI = 2.77–3.47; burden = 33.85, 95% CI = 28.55–39.74), fatigue (HR = 2.33, 95% CI = 2.14–2.53; burden = 46.92, 95% CI = 40.46–53.89), gastrointestinal disorders (HR = 2.48, 95% CI = 2.35–2.62; burden = 100.30, 95% CI = 91.88–109.09), kidney disorders (HR = 3.55, 95% CI = 3.18–3.97; burden = 38.31, 95% CI = 32.86–44.37), mental health disorders (HR = 2.14, 95% CI = 2.04–2.24; burden = 116.13, 95% CI = 106.71–125.87), diabetes (HR = 1.70, 95% CI = 1.41–2.05; burden = 6.46, 95% CI = 3.77–9.69), musculoskeletal disorders (HR = 1.64, 95% CI = 1.49–1.80; burden = 25.55, 95% CI = 19.73–31.91) and neurological disorders (HR = 1.60, 95% CI = 1.51–1.69; burden = 52.91, 95% CI = 45.48–60.70). Risks and excess burdens of reinfection are provided in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3. Analyses examining whether the length of time from first infection to reinfection might modify the association between reinfection and the risks of all-cause mortality, hospitalization and at least one sequela suggested no effect modification on the multiplicative scale (P values for effect modification of 0.224, 0.156 and 0.356, respectively).

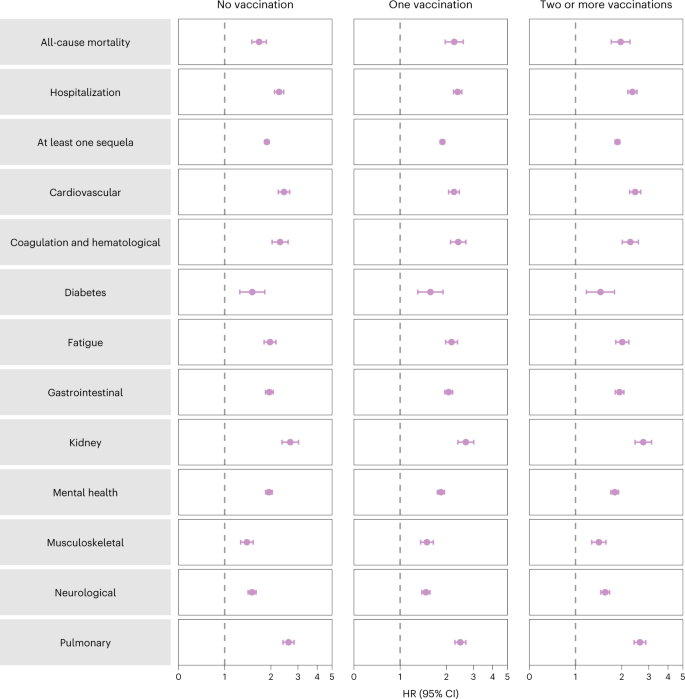

Analyses of prespecified subgroups based on vaccination status before reinfection (no vaccination, one vaccination or two or more vaccinations) showed that reinfection (compared to no reinfection) was associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality, hospitalization, at least one sequela and sequelae in the different organ systems (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 4) regardless of vaccination status.

Risk of all-cause mortality, hospitalization, at least one sequela and sequelae by organ system are plotted. Incident outcomes were assessed from reinfection to the end of the follow-up. Results from SARS-CoV-2 reinfection (n = 40,947) versus no SARS-CoV-2 reinfection (n = 443,588) are compared. At the time of comparison, there were 51.3%, 12.6% and 36.2% with no, one and two or more vaccinations, respectively, among those who had reinfection. At the time of comparison, there were 41.1%, 11.7% and 47.2% with no, one and two or more vaccinations, respectively, among the no reinfection group. Adjusted HRs (dots) and 95% CIs (error bars) are presented.

Acute and postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection

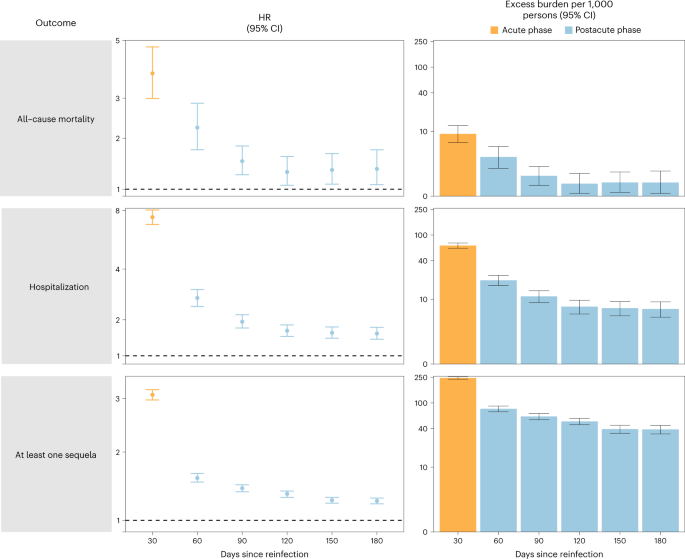

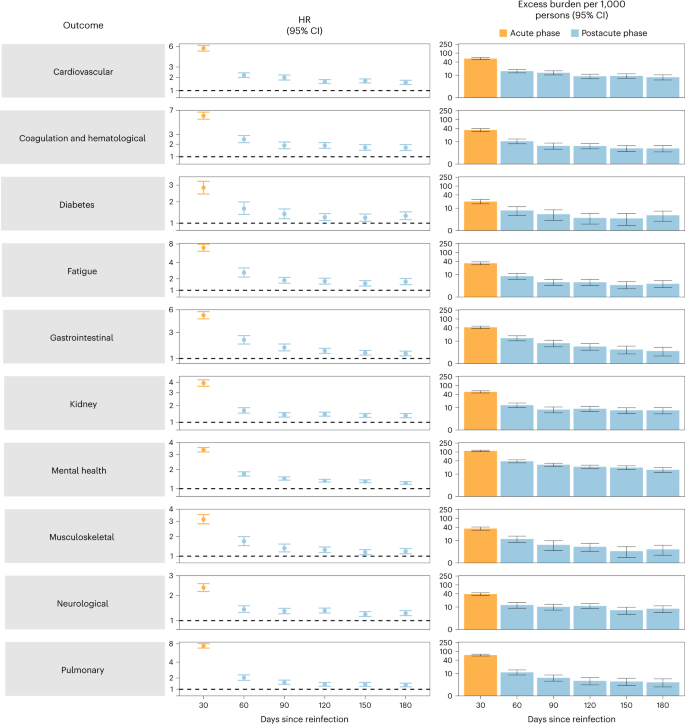

We examined whether the risk of sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection was present in the acute and postacute phases of reinfection. We conducted analyses examining risk and burden starting from the time of reinfection up to 180 d later in 30-day increments. Compared to those with no reinfection, those who had reinfection exhibited increased risk and excess burden of all-cause mortality, hospitalization and at least one sequela in the acute and postacute phases of reinfection. The risks and excess burdens of all-cause mortality, hospitalization and at least one sequela during the postacute phase gradually attenuated over time but remained evident even 6 months after reinfection (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 5). Examination of sequelae by organ system suggested an increased risk and excess burden in all organ systems during the acute phase (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 5). The risks and burdens persisted in the postacute phase of reinfection and were still evident at 6 months after reinfection.

Risk and 6-month burden of all-cause mortality, hospitalization and at least one sequela of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection versus no reinfection in 30-d intervals covering the acute and postacute phases of reinfection. Incident outcomes were assessed from reinfection to the end of the follow-up. Results from SARS-CoV-2 reinfection (n = 40,947) versus first SARS-CoV-2 infection (n = 443,588) by time since reinfection were compared. Adjusted HRs (dots) and 95% CIs (error bars) are presented for each 30-d period since the time of reinfection, as are the estimated excess burden (bars) and 95% CIs (error bars). Burdens are presented per 1,000 persons at every 30-d period of the follow-up from the time of reinfection.

Risk and 6-month excess burden of sequelae by organ system of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection versus no reinfection in 30-d intervals covering the acute and postacute phases of reinfection. Incident outcomes were assessed from reinfection to the end of the follow-up. Results from SARS-CoV-2 reinfection (n = 40,947) versus first SARS-CoV-2 infection (n = 443,588) by time since reinfection are compared. Adjusted HRs (dots) and 95% CIs (error bars) are presented for each 30-d period since the time of reinfection, as are the estimated excess burden (bars) and 95% CIs (error bars). Burdens are presented per 1,000 persons at every 30-d period of the follow-up from the time of reinfection.

Cumulative risk and burden of one, two and three or more SARS-CoV-2 infections

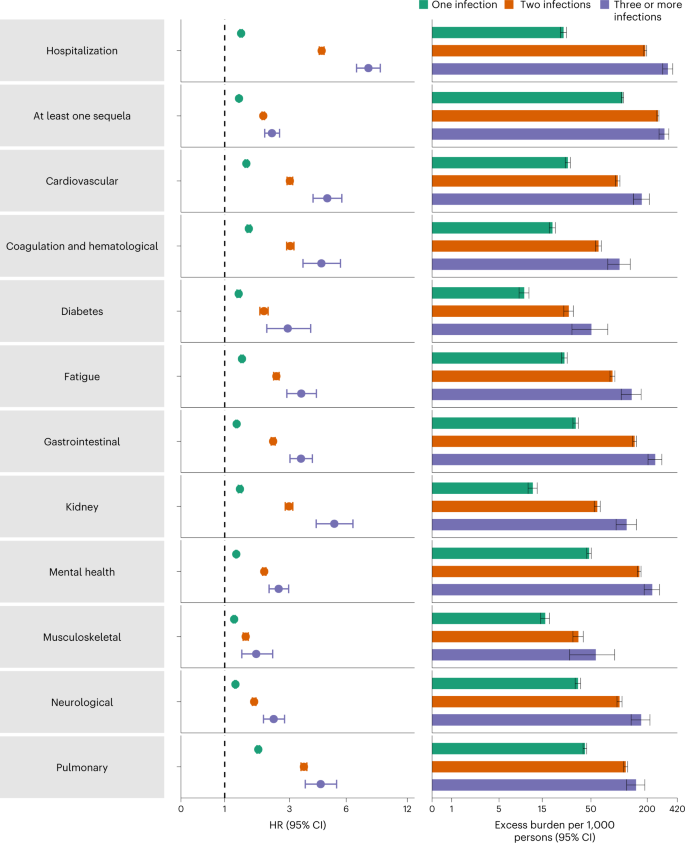

To better understand the cumulative risks incurred by people with multiple infections, we estimated the cumulative risk and burden of a set of prespecified outcomes in those who did not have a reinfection (had only one infection), and those who had two or three or more infections during the 1-year period after the acute phase of the first infection, compared to a noninfected control group. Cohort characteristics are provided in Supplementary Table 6. There was a graded association in that the risks of adverse health outcomes increased as the number of infections increased. Compared to the noninfected control group, those who only had one infection had an increased risk of at least one sequela (HR = 1.37, 95% CI = 1.36–1.38; burden per 1,000 persons at one-year = 108.88, 95% CI = 105.89–111.87); the risk was higher in those who had two infections (HR = 2.07, 95% CI = 2.03–2.11; burden = 260.41, 95% CI = 253.70–267.09) and highest in those with three or more infections (HR = 2.35, 95% CI = 2.12–2.62; burden = 305.44, 95% CI = 268.07–341.11). In a pairwise comparison of those with two infections versus one infection, those with two infections had an increased risk of at least one sequela (HR = 1.51, 95% CI = 1.48–1.54; burden = 151.53, 95% CI = 144.83–158.21); in pairwise comparison of those with three or more infections versus those with only two infections, those with three or more infections had a higher risk of at least one sequela (HR = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.02–1.27; burden = 45.02, 95% CI = 7.66–80.70). Results were consistent when hospitalization and sequelae by organ system were examined (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Tables 7–12).

Risk and 1-year excess burden of hospitalization, at least one sequela and sequelae by organ system are plotted. Incident outcomes were assessed from 30 d after the first positive SARS-CoV-2 test to the end of the follow-up. Results from one SARS-CoV-2 infection (n = 234,990), two SARS-CoV-2 infections (n = 28,509) and three or more SARS-CoV-2 infections (n = 1,023) versus noninfected controls (n = 5,334,729), in those with a first infection before the Omicron wave, are compared. Adjusted HRs (dots) and 95% CIs (error bars) are presented, as are the estimated excess burden (bars) and 95% CIs (error bars). Burdens are presented per 1,000 persons at 1 year of follow-up.

Positive and negative outcome controls

We conducted a positive outcome control analysis to examine whether our approach reproduced previous established knowledge, testing whether the association of a SARS-CoV-2 infection (irrespective of reinfection) was associated with risk of fatigue (a well-characterized, cardinal postacute sequela of COVID-19, where a positive association would be expected based on previous evidence). Results showed that, compared to a noninfected control group, those with a SARS-CoV-2 infection exhibited an increased risk of fatigue (HR = 1.72, 95% CI = 1.70–1.74).

We then conducted a set of negative outcome control analyses to test for the potential presence of spurious associations using the same data sources, cohort construction processes, covariate selections and definitions (including predefined and algorithmically selected high-dimensional covariates), covariate balance methods and result interpretations as those of our primary analysis. Results examining the risk of atopic dermatitis and neoplasms (negative outcome controls), where there was no previous biological or epidemiological evidence to suggest an association should be expected, did not show a significant association in those who had reinfection compared to those with no reinfection (HR = 1.06, 95% CI = 0.91–1.24 and HR = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.97–1.10, respectively).

Discussion

In this study of 5,819,264 people, including 443,588 people with a first infection, 40,947 people who had reinfection and 5,334,729 noninfected controls, we showed that compared to people with no reinfection, people who had reinfection exhibited increased risks of all-cause mortality, hospitalization and several prespecified outcomes. The risks were evident in those who were unvaccinated and had one vaccination or two or more vaccinations before reinfection. The risks were most pronounced in the acute phase but persisted in the postacute phase of reinfection, and risks for all sequelae were still evident at 6 months. Compared to noninfected controls, assessment of the cumulative risks of repeat infection showed that the risk and burden of all-cause mortality and the prespecified health outcomes increased in a graded fashion according to the number of infections (that is, risks were lowest in people with one infection, increased in people with two infections and were highest in people with three or more infections). Altogether, the findings show that reinfection further increases risks of all-cause mortality and adverse health outcomes in both the acute and postacute phases of reinfection. The findings highlight the clinical consequences of reinfection and emphasize the importance of preventing reinfection by SARS-CoV-2.

Estimates suggest that more than half a billion people around the globe have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 at least once11. For the large and growing number of people who encountered a first infection, the question of whether a second infection carries additional risks is important. In this work, we showed that reinfection further increases risks of all-cause mortality and adverse health outcomes in both the acute and postacute phases of reinfection, suggesting that for people who have already been infected once, continued vigilance to reduce the risk of reinfection may be important to lessen the overall risk to one’s health.

Given the likelihood that SARS-CoV-2 will continue to mutate and might remain a threat for years if not decades, leading to the emergence of variants or subvariants that might be more immune-evasive, and given that reinfections are occurring and might continue to occur due to these emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants at scale in many countries across the globe, and given that reinfection contributes nontrivial health risk both in the acute and postacute phases, a strategy that would result in vaccines that are more durable, cover a broad array of variants (variant-proof vaccine strategy), reduce transmission (and subsequently reduce the risk of infection and reinfection) and reduce both acute and long-term consequences in people who get infected or reinfected is urgently needed12. Other pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical interventions to lessen both the risk of reinfection and its adverse health consequences are also urgently needed.

Questions have been raised with regard to whether reinfection increases the risk of long COVID—the umbrella term encompassing the postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Our results show that beyond the acute phase, reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 contributes substantial additional risks of all-cause mortality, hospitalization and postacute sequelae in the pulmonary and broad array of extra pulmonary organ systems.

The mechanisms underpinning the increased risks of death and adverse health outcomes in reinfection are not completely clear. Previous exposure to the virus may be expected to hypothetically reduce risk of reinfection and its severity9,13; however, SARS-CoV-2 is mutating rapidly and new variants and subvariants are replacing older ones every few months. Evidence suggests that the reinfection risk is especially higher with the Omicron variant, which was shown to have a marked ability to evade immunity from previous infection10,14. Any protection from previous infection (against reinfection and its severity) also wanes over time10; evidence suggests that protection from reinfection declined as time increased since the last immunity-conferring event in people who had previously been infected with SARS-CoV-2, regardless of vaccination status15. Furthermore, impaired health as a consequence of the first infection might result in increased risk of adverse health consequences upon reinfection. Our results expand this evidence base and show that in people who get reinfected, reinfection (compared to no reinfection) further increases risk in both the acute and postacute phases and that this was evident even among fully vaccinated people, suggesting that even combined (a hybrid of) natural immunity (from previous infection) and vaccine-induced immunity does not abrogate the risk of adverse health effects after reinfection. The totality of evidence suggests that strategies to prevent reinfection might benefit people regardless of previous history of infection and vaccination status.

This study has several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first study to characterize both the short- and long-term health risks of reinfection. We used the US Department of Veterans Affairs national healthcare database (the largest nationally integrated healthcare delivery system in the US) to undertake the analyses. We used advanced statistical methodologies and adjusted through weighting for a set of predefined covariates selected based on previous knowledge and algorithmically selected covariates from high-dimensional data domains including diagnoses, prescription records and laboratory test results. Because the virus is mutating over time and the proportion of different variants may vary geographically, and because different variants may have different effects on outcomes, we further adjusted our analyses for measures of the time and geographical region where participants first tested positive for SARS-Cov-2 and additionally for the proportions of each variant at the time and region of their first infection. We evaluated both acute and postacute outcomes of reinfection and examined risks according to vaccination status before reinfection. We evaluated the rigor of our approach by testing positive and negative outcome controls to determine whether our approach would produce results consistent with pretest expectations.

The study has several limitations. The cohorts of people with one, two, three or more infections included those that had a positive test for SARS-CoV-2 and did not include those who may have had an infection with SARS-CoV-2 but were not tested; this may have resulted in misclassification of exposure since these people would have been enrolled in the control groups. If present in large numbers and if their true risk of adverse health outcomes is substantially higher than the noninfected controls, then this may have resulted in underestimation of the risks of reinfection. Although we leveraged several Veterans Affairs and non-Veterans Affairs data sources, our datasets may not have comprehensively captured care received outside the Veterans Affairs (including exposure (positive SARS-CoV-2), covariates (for example, vaccination) and outcomes), which may contribute to potential misclassification. Although the Veterans Affairs population which consists of those who are mostly older and male may not be representative of the general population, our cohorts included 10.3% women, which amounted to 589,573 participants, and 12% were under 38.8 years of age (the median age of the US population in 2021), which amounted to 680,358 participants. Subgroup analyses were not conducted by age, sex and race. Although we balanced characteristics of the exposure groups through weighting using a set of predefined and algorithmically selected covariates, which included demographic, behavioral, contextual and clinical characteristics, we cannot completely rule out residual confounding from unmeasured or otherwise unknown confounders. The COVID-19 pandemic is a highly dynamic global event that is still unfolding in real time; as various epidemiological drivers of this pandemic change over time (including emergence of new variants, increase in vaccine uptake and waning vaccine immunity), it is likely that the epidemiology of reinfection and its health consequences may also change over time. The aim of our analyses was to examine the health risks associated with those individuals who had reinfection (compared to no reinfection). Our analyses should not be interpreted as an assessment of severity of a second infection versus that of a first infection, nor should they be interpreted as an examination of the risks of adverse health outcomes after a second infection compared to risks incurred after a first infection. Our analyses do not provide a comparative assessment of the risks of reinfection with different variants or subvariants.

In sum, in this study of 5,819,264 individuals, we provide evidence that reinfection contributes to additional health risks beyond those incurred in the first infection including all-cause mortality, hospitalization and sequelae in a broad array of organ systems. The risks were evident in the acute and postacute phases of reinfection. The evidence suggests that for people who already had a first infection, prevention of a second infection may protect from additional health risks. Prevention of infection and reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 should continue to be the goal of public health policy.