Finally, a picture of a different virus.

The flu season usually begins in the Southern Hemisphere before moving North. That’s why Australia’s flu season usually predicts ours. When the pandemic hit and everything was shut down, so did the flu. We didn’t have any. The following is an article from the International Laboratory News. Following that it everything you every wanted to know about the flu vaccines available from the Medical Letter.

Bottom line: Get a flu vaccine in the next few weeks.

End of social distancing, masking, and other COVID-19 pandemic mitigations may lead to more severe flu-like infections in northern hemisphere, experts say

Clinical laboratory professionals in the United States and Canada should prepare now for a severe flu season. That is according to infectious disease experts at Johns Hopkin’s Center for Health Security who predict the rise in influenza (flu) cases in Australia signals what will likely be higher than normal numbers of flu-like infections starting this fall in the Northern Hemisphere.

As a Southern Hemisphere nation, Australia experiences winter from June through August. The land down under just concluded its worst flu season in five years. The flu arrived earlier than usual and was severe. Surveillance reports from the Aussie government’s Department of Health and Aged Care noted that influenza-like illness (ILI) peaked in May and June, but that starting in mid-April 2022 the weekly number of flu cases exceeded the five-year average.

If the same increase in flu cases happens here, healthcare systems and clinical laboratories already burdened with continuing COVID-19 testing and increasing demand for monkeypox testing could find the strain unbearable.

Amesh Adalja, MD (above), Infectious Disease Expert and Senior Scholar at the Johns Hopkin’s Center for Health Security, told Prevention that Australia’s flu season is typically a harbinger of what will follow in the US, Canada, and other Northern Hemisphere countries. “The planet has two hemispheres which have opposite respiratory viral seasons,” he said. “Therefore, Australia’s flu season—which is just ending—is often predictive of what will happen in the Northern Hemisphere.” Clinical laboratories in the United States should review their preparations as North America enters its influenza season. (Photo copyright: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.)

Consequences of Decline in Flu Vaccinations and Social Distancing, Masks

The New York Times noted that in 2017, when Australia suffered through its worst flu season since modern surveillance techniques were adopted, the US experienced a deadly 2017-2018 flu season a half-year later that took an estimated 79,000 lives.

While the number of flu cases in this country is currently low, according to the weekly US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) “Flu View,” that is expected to change as temperatures cool.

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US, influenza was nearly nonexistent. Pandemic-mitigation efforts such as masking, social distancing, and quarantining slowed the spread of the annual respiratory illness. But pandemic mitigation efforts are no longer the norm.

“Many have stopped masking,” said Abinash Virk MD, an Infectious Diseases Specialist at Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, in a Mayo Clinic news blog that urged patients to get vaccinated for flu. “For the large part, we will see the re-emergence of influenza in the winter. In comparison, in 2020 winter … there was literally no influenza. But now that has all changed.”

Diminished Immunity Will Lead to More Severe Flu Cases

A CDC report published in July also noted that last winter’s flu season broke from the traditional pattern of arrival of the flu in the fall followed by a peak in cases in February.

During the 2021-22 season, influenza activity began to increase in November and remained elevated until mid-June. It featured two distinct waves, with A(H3N2) viruses predominating for the entire season. But the overall case counts were the lowest in at least 25 years preceding the COVID-19 pandemic.

Thomas Russo, MD, Professor and Chief of Infectious Disease at the University at Buffalo in New York, said the past two mild flu seasons could set the stage for a difficult year in 2022-23.

“Immunity to respiratory viruses, including the flu, wanes over time,” Russo told Prevention. “People have not seen the virus naturally for a couple of years and many individuals don’t get the flu vaccine.” That, he says, raises the risk that people who are unvaccinated against the flu will develop more severe cases if they do happen to get infected.

“People are interacting closely again and there are very few mandates,” he added. “That’s a set-up for increased transmission of influenza and other respiratory viruses.”

Anthony Fauci, MD, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), warns the US could see higher than normal rates of influenza while COVID-19 is still circulating widely.

“The Southern Hemisphere has had a pretty bad flu season, and it came on early,” Fauci, told Bloomberg in late August. “Influenza, as we all have experienced over many years, can be a serious disease, particularly when you have a bad season.”

CNN reported that US government modeling predicts flu will peak this year in early December.

CDC Advises Public to Get Flu Vaccine

Because COVID-19 and Influenza have many symptoms in common, such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, fatigue, sore throat, runny nose, headache, and muscle aches, the Mayo Clinic points out on its blog that testing is the only way to discern between the two when symptoms overlap.

According to the CDC, the best way to reduce risk from seasonal flu and its potentially serious complications is to get vaccinated every year. The best time to get vaccinated for the flu is in September and October before the flu starts spreading in communities, the CDC states. However, vaccination after October can still provide protection during the peak of flu season.

Yet, many people fail to get the flu vaccine even though it is recommended for everyone over the age of six months. CNN reported that just 45% of Americans got their flu shots last season. Flu vaccination rates fell for several at-risk groups, including pregnant women and children.

Though flu seasons are often unpredictable, clinical laboratories should prepare now for an influx of influenza test specimens and higher case rates than the past two pandemic-lightened flu seasons. Coupled with COVID-19 and monkeypox testing, already strained supply lines may be disrupted.

—Andrea Downing Peck

ISSUE

1660

Key Points: Influenza Vaccine for 2022-2023

- Annual vaccination in the US against influenza A and B viruses is recommended for everyone ≥6 months old without a contraindication.

- Vaccination should ideally be offered in September or October and continue to be offered as long as influenza viruses are circulating in the community.

- All influenza vaccines available in the US this season are quadrivalent; they contain two influenza A and two influenza B virus antigens.

- Influenza vaccination reduces the incidence of laboratory-confirmed influenza and the risk of serious complications and death associated with influenza illness.

- In adults ≥65 years old, use of a high-dose, adjuvanted, or recombinant vaccine can improve immune responses and is preferentially recommended over other influenza vaccines.

- Pregnant women in any trimester should be vaccinated against influenza.

- The ACIP states that persons with a history of egg allergy can receive any age-appropriate influenza vaccine, but those with a history of severe egg allergy who receive an egg-based vaccine should be vaccinated in a medical setting supervised by a healthcare provider experienced in managing severe allergic reactions.

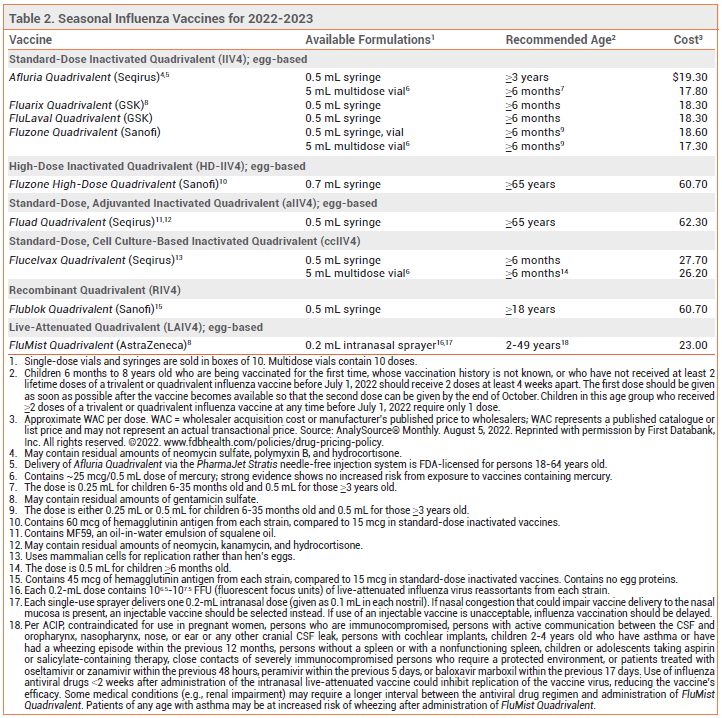

Annual vaccination in the US against influenza A and B viruses is recommended for everyone ≥6 months old without a contraindication.1 Influenza vaccines that are available in the US for the 2022-2023 season are listed in Table 2.

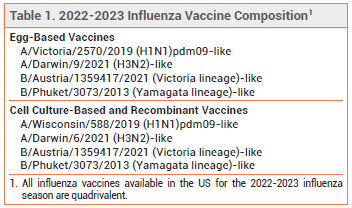

COMPOSITION — All influenza vaccines available in the US this season are quadrivalent; they contain two influenza A and two influenza B virus antigens (see Table 1). Influenza A viruses are the main cause of influenza-related morbidity and mortality, especially in older adults. Influenza B illness is usually more severe in children, especially those <5 years old.2

TIMING — In the US, vaccination against influenza should ideally be offered in September or October and continue to be offered as long as influenza viruses are circulating in the community. In most adults, serum antibody levels peak 1-2 weeks after vaccination. Early vaccination (i.e., in July or August) may result in suboptimal immunity before the end of the influenza season, especially in older adults.3

The ACIP specifically recommends that pregnant women who are in the first or second trimester during July or August wait until September or October to be vaccinated, unless vaccination later is not possible; vaccination during July or August can be considered for women who are in their third trimester.1

Children who require 2 doses (see Table 2, footnote 2) should receive the first dose as early as possible so that the second dose can be given by the end of October.

For persons with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19, vaccination should be postponed until the isolation period has ended.4

EFFECTIVENESS — Influenza vaccination reduces the incidence of laboratory-confirmed influenza and the risk of serious complications and death associated with influenza illness.5-8 The effectiveness of the seasonal influenza vaccine in preventing influenza illness depends on several factors, including the match between the vaccine and circulating strains and the immunologic response of the recipient. Vaccine effectiveness is greatest when the match is close, but even when it is suboptimal, vaccination still can substantially reduce the risk of influenza-related hospitalization and death.9,10

OLDER ADULTS — Older adults are at increased risk for severe influenza-associated illness, hospitalization, and death. They may have weaker immunogenic responses to influenza vaccination than younger persons, and their antibody levels may decline more rapidly, decreasing vaccine effectiveness.11

In a cohort study of hospitalized adults ≥60 years old with cardiovascular disease, influenza vaccination was associated with a reduced risk of in-hospital mortality. It was also associated with a lower risk of recurrent hospitalization and respiratory disease in patients with ischemic heart disease.12

High-Dose Vaccine – Fluzone High-Dose Quadrivalent, an inactivated vaccine that contains 4 times the amount of antigen included in standard-dose inactivated influenza vaccines, is FDA-licensed for use in persons ≥65 years old.

In a randomized, double-blind trial in 31,989 adults ≥65 years old during 2 influenza seasons, a high-dose inactivated trivalent vaccine (Fluzone High-Dose; no longer available) induced significantly greater antibody responses than a standard-dose inactivated trivalent vaccine and was 24% more effective in preventing laboratory-confirmed influenza illness.13 In several studies in adults ≥65 years old, use of a high-dose inactivated trivalent vaccine was associated with a reduced risk of respiratory-related and all-cause hospitalization and death compared to standard-dose inactivated trivalent vaccines.14-17

In a randomized trial in 5260 patients with high-risk cardiovascular disease, use of a high-dose inactivated trivalent vaccine over 3 influenza seasons did not significantly reduce all-cause mortality or cardiopulmonary hospitalizations compared to standard-dose inactivated quadrivalent vaccines.18

Adjuvanted Vaccine – Fluad Quadrivalent, an adjuvanted inactivated influenza vaccine, is FDA-licensed for use in persons ≥65 years old. It contains MF59, an oil-in-water emulsion of squalene oil that increases the immune response by recruiting antigen-presenting cells to the injection site and promoting uptake of influenza virus antigens.

In a randomized trial in 7082 adults ≥65 years old, an adjuvanted inactivated trivalent vaccine (Fluad; no longer available) elicited significantly greater antibody responses against all three influenza strains than a nonadjuvanted inactivated trivalent vaccine.19 In several trials, older adults who received an adjuvanted inactivated trivalent vaccine were less likely to develop symptomatic influenza illness or to be hospitalized for influenza or pneumonia than those who received a nonadjuvanted inactivated trivalent vaccine.20-22

Recombinant Vaccine – Flublok Quadrivalent, a recombinant influenza vaccine produced without the use of influenza virus or chicken eggs, contains 3 times the amount of antigen included in standard-dose inactivated influenza vaccines. It is FDA-licensed for use in persons ≥18 years old.

In a randomized, double-blind trial in 8604 adults ≥50 years old during the A/H3N2-predominant 2014-2015 influenza season, the recombinant quadrivalent vaccine was 30% more effective than a nonadjuvanted standard-dose inactivated quadrivalent vaccine in preventing laboratory-confirmed influenza illness.23

Choice of Vaccine – In a recent trial in community-dwelling adults 65-82 years old, high-dose, adjuvanted, and recombinant influenza vaccines improved humoral and cell-mediated immune responses compared to standard-dose inactivated vaccines.24 Few trials have directly compared the high-dose, adjuvanted, and recombinant vaccines in older adults and none have shown that any one vaccine is superior to another.

For the first time, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) is recommending use of a high-dose, adjuvanted, or recombinant influenza vaccine over other available age-appropriate influenza vaccines in adults ≥65 years old; if one of these vaccines is not available, vaccination should not be delayed and a standard-dose, nonadjuvanted vaccine should be given.1

PREGNANCY — Vaccination protects pregnant women against influenza-associated illness, which can be especially severe during pregnancy, and protects their infants for up to 6 months after birth (influenza vaccines are not approved for use in infants <6 months old).25 The ACIP and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommend that pregnant women be vaccinated against influenza without regard to the trimester of pregnancy (see Timing section).26,27 Pregnant women can receive any age-appropriate inactivated or recombinant influenza vaccine; the intranasal live-attenuated vaccine (FluMist Quadrivalent) should not be used during pregnancy.

Most studies have not found an association between influenza vaccination and adverse pregnancy outcomes, but data demonstrating the safety of vaccination during the first trimester are limited.28

EGG ALLERGY — The recombinant vaccine (Flublok Quadrivalent) and the cell culture-based inactivated vaccine (Flucelvax Quadrivalent) do not contain egg protein. Other available influenza vaccines may contain trace amounts of egg protein (ovalbumin), but numerous studies have found that patients with a history of egg allergy are not at increased risk for a reaction to influenza vaccines that are propagated in eggs.29

The ACIP states that persons with a history of egg allergy of any severity can receive any age-appropriate influenza vaccine, but those with a history of more severe egg allergy (angioedema, respiratory distress, light headedness, recurrent vomiting, or requiring epinephrine or another emergency medical intervention) who receive an egg-based vaccine should be vaccinated in a medical setting (e.g., doctor’s office or clinic) supervised by a healthcare provider experienced in managing severe allergic reactions.1

The Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters of the American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology and the American College of Allergy Asthma and Immunology state that no special precautions are necessary for patients with egg allergy of any severity.30 The American Academy of Pediatrics adds that it is not necessary to inquire about egg allergy before administration of any influenza vaccine, including on screening forms.31

IMMUNOCOMPROMISED PERSONS — The live-attenuated influenza vaccine should not be used in immunocompromised persons. Inactivated and recombinant vaccines are generally considered safe for use in such persons, but the immune response may be reduced. In two randomized trials in solid-organ transplant recipients, the high-dose vaccine induced significantly greater immune responses than standard-dose vaccines.32,33 Separating the time of influenza vaccination from that of an immunocompromising intervention might be considered.

USE WITH OTHER VACCINES — Any influenza vaccine can be given at the same time as a COVID-19 vaccine, but the vaccines should be administered at different sites. Inactivated and recombinant influenza vaccines can be administered concomitantly or sequentially with live or other inactivated or recombinant vaccines. The live-attenuated influenza vaccine can be given simultaneously with inactivated or other live vaccines; other live vaccines not administered simultaneously should be given at least 4 weeks later. Use of a nonadjuvanted influenza vaccine could be considered in persons receiving an adjuvanted non-influenza vaccine (e.g., Shingrix, Heplisav-B); coadministration of Shingrix and a nonadjuvanted inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine has not been associated with a decrease in the immunogenicity of either vaccine or safety concerns.34

USE WITH INFLUENZA ANTIVIRALS — Use of oseltamivir (Tamiflu, and generics) or zanamivir (Relenza) within 48 hours before, peramivir (Rapivab) within 5 days before, or baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza) within 17 days before administration of the intranasal live-attenuated influenza vaccine could inhibit replication of the vaccine virus, reducing the vaccine’s efficacy. Persons who receive any of these antiviral drugs during these specified times and through 2 weeks after receiving the live-attenuated vaccine should be revaccinated with an inactivated or recombinant influenza vaccine.

ADVERSE EFFECTS — Influenza vaccination has been associated with Guillain-Barré syndrome, but the absolute risk is very low (about 1-2 additional cases per million persons vaccinated), and influenza infection itself has been associated with the syndrome (about 17 cases per one million patients hospitalized with influenza).35 In a prospective cohort study in patients with diabetes, influenza vaccination was associated with hyperglycemia, but serum glucose levels returned to baseline 2 days post-vaccination.36

Except for soreness at the injection site, adverse reactions to inactivated influenza vaccines are uncommon. In clinical trials, the trivalent formulation of Fluzone High-Dose (no longer available) caused more injection-site reactions than standard-dose influenza vaccines. Pain and tenderness at the injection site also occurred more frequently with Fluad (adjuvanted trivalent) than with a nonadjuvanted vaccine. Delivery of Afluria by needle-free jet injector has resulted in more mild to moderate local reactions than delivery by standard needle and syringe.

The most common adverse reactions associated with the live-attenuated vaccine are runny nose, nasal congestion, fever, and sore throat. The vaccine may increase the risk of wheezing, especially in children <5 years old with recurrent wheezing and in persons of any age with asthma. A recent study, however, in 151 children with asthma found that the risk of asthma exacerbations was similar with the live-attenuated influenza vaccine and a quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine.37 Persons who receive the live-attenuated vaccine may shed the vaccine-strain virus for a few days after vaccination, but person-to-person transmission has been rare, and serious illness resulting from transmission has not been reported. Nevertheless, the ACIP states that persons who care for severely immunocompromised patients in protected environments should not receive the live-attenuated vaccine or should avoid contact with such patients for 7 days after receiving it.

INVESTIGATIONAL VACCINES – Vaccines that provide universal protection against all influenza strains are in development. A vaccine designed to protect against influenza, COVID-19, and respiratory syncytial virus, the three primary causes of viral respiratory disease in older adults, and a vaccine against both influenza and COVID-19 are also in development.